Read about the two other mistakes we made here:

What was our business?

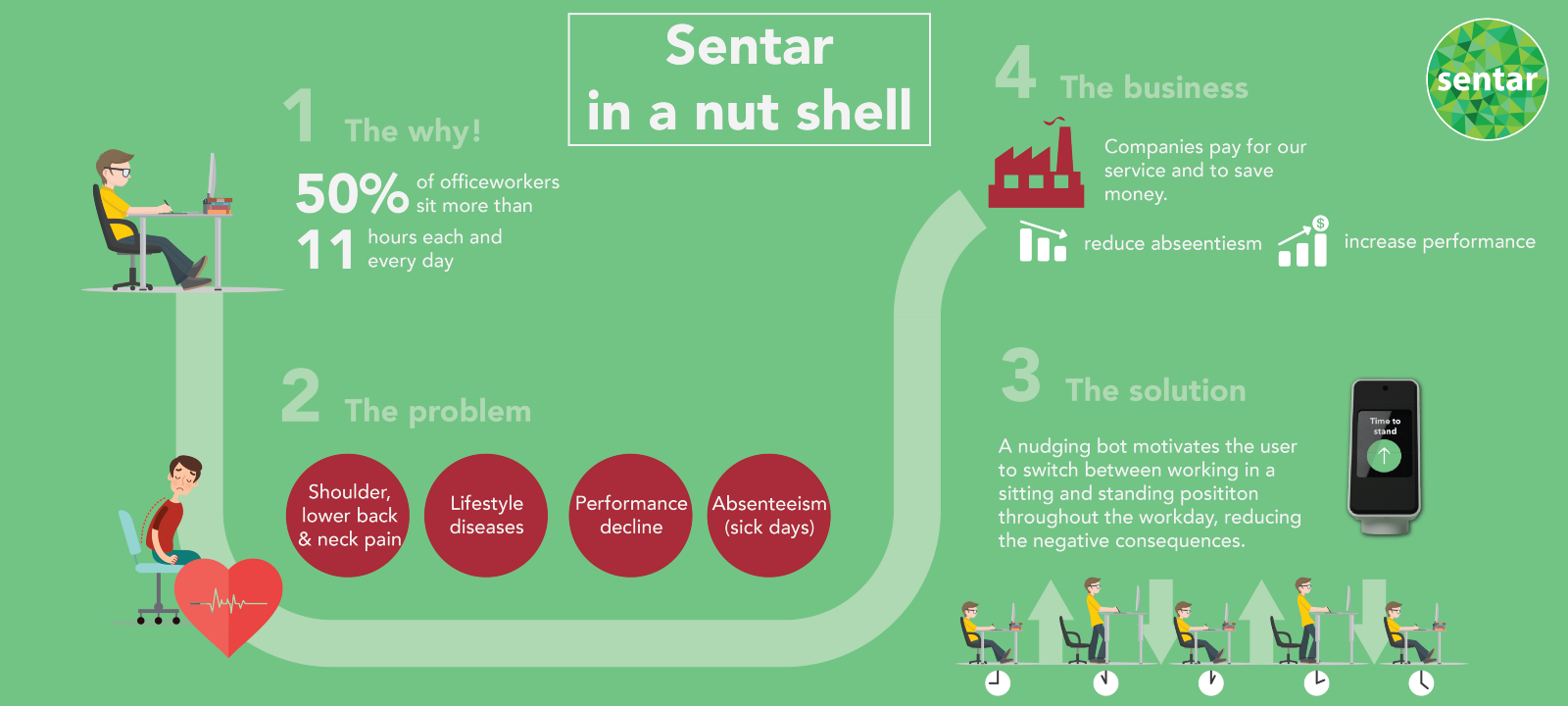

First things first. We tried to make office workers sit less, to improve employee health and avoid incapacity. Our solution should be the cost-effective B2B alternative to hire an occupational therapist providing individual coaching. We wanted to do it the tech way — the scalable way.

So our solution was to make a small hardware bot, which would make the office workers use their elevation desk to shift between sitting and standing more often (9/10 desks are elevation desks in Scandinavia) and thereby eliminate most of the negative consequences of sitting down all day (also called sedentary behaviour). We have illustrated the problem and our solution below:

So why did we end up making the mistake of trying too hard to validate the need for our product?

Reason #1: the dilemma of “Making it happen” vs. “Validating the need for your product”

When trying to validate a need for something you carry out an experiment. You try to sell a solution to a group of customers with a shared problem/need, and the outcome of the experiment should end up either verifying, dismissing or changing your hypothesis. You have to be ready for all outcomes, which we as a team were not. We wanted it to work out – somehow.

Internally this ended up in a discussion about whether you are a pessimist or and optimist. In our case our business guy was the personification of the typical pessimist and the product guys the typical optimists.

One side of the discussion was represented by our business guy, who kept coming back from customer interviews and market research with negative feedback. The other side was represented by the product guys, who argued that it was just a matter of making it happen, that the problem was clear and therefore, someone will pay for our solution.

Arguments for “making it happen” (Product team)

- The first 10 startup analogies on founders who thought everything was against them, kept going and now they are billionaires (Take ALIBABA founder Jack Ma as an example).

- Maybe we are selling our value proposition wrong

- We just have to make a product that users love, then we will be able to sell it somehow

- Behavioural change (making office workers sit less) is super hard

- If we can nail this with our product, someone will pay for it

Arguments for “validating the need for our solution” (Business guy)

- 9/10 startups fail, 43% of these say they fail due to “no market need” — therefore our #1 priority is to make sure we have a market need

- Why build something, even prototypes, if we can’t sell it?

- Our business case is not clear for our customers and it is not feasible for us to build a business case first and then educate our customers afterwards

Both parties in the discussion could understand the other party’s point of view, which made it hard to conclude anything. We ended up spending much more time on product development than on business development, so in that sense the product development team “won” the discussion.

When looking back we can conclude that every early-stage startup should focus all their energy on whether or not there is a business need for their solution. We honestly feel that the thousands of hours spend on prototyping was a waste of time, now that we concluded not enough customers felt our solution was worth paying for.

We also concluded that if you have to choose between being a pessimist or optimist when trying to validate the need for your solution, you should choose to be a pessimist — the next reason will explain why.

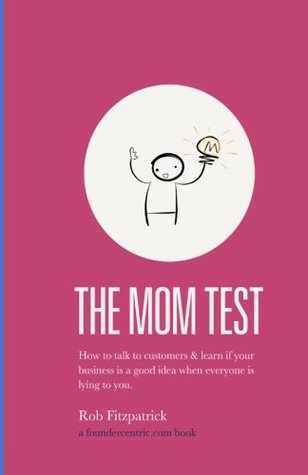

Reason #2: the MOM-test

Without going too much into sociology and the complexity of human interactions, the second reason why we made the mistake: “Trying too hard to validate the need for your product” in Sentar, is justified in what happens when humans interact.

Basically when people interact they want to “save face”. It means to preserve one’s own and others’ dignity. We do not want to make each other embarrassed, by telling someone that the product they are presenting doesn’t make sense. In the startup world this mechanism is sometimes referred to as the MOM-test. Remember that super ugly drawing you brought home as a 4-year old, which your mom proclaimed to be an artistic master piece?

Your mom will lie to you about how good you are, and customers will lie to you about what they think of your product. Yeah tough luck. We know.

Take one of our first meetings with PFA Pension (Large Danish Pension & Insurance company) as an example of this. This is what happened:

- We present the problem with statistical numbers stating that lower back pain and sedentary behaviour is a big problem

- We ask them if they also see it as a big problem: “Yes yes, very big problem”

- We present our solution to this problem and our price model (this is before we had developed anything)

- They like the solution and say that they might push it to their insurance customers if the product delivers what it promises

- They agree to collaborate as a test company without charges, so that they can see first hand if this is a product they would recommend their customers

We thought this was positive. Maybe you do as well? We became wiser. Everything that PFA had committed to and acknowledged was 100% “free”. 1 month later they jumped ship with the excuse of some IT department problems.

Let’s take a look at what this really means:

- We present them hardcore facts face to face at the meeting. Naturally they will agree that statistically our problem is a problem

- We present them an idea we obviously have spent some time developing, and to appear sympathetic and make us happy, they avoid being critical

- They state that if we can develop a solution which will do great things, they will NOT pay for it, but only recommend it to their clients

- They agree to test with us which only costs them “hours”

So what really happens here, is that we analyse the outcome of this meeting to be VERY positive. But really they have not validated they have a business problem here. What we have validated is that a pension company, would like to have a product like ours to offer their clients — but without paying anything. Thus, the product did not solve a business need for PFA worth paying for.

Looking back we conclude that we should have pushed our clients much harder in these initial meetings. We should have talked money from day 1 and asked them to pay for it. This way we would have made PFA say: “Guys, it’s a nice solution and all, but we can’t really pay for it, as the problem you are solving is not something we can spend money on right now. It is simply not that valuable to our core business”.

But we didn’t. And we are not the first ones that fail at doing so.

This is one of the reasons why Rob Fitzpatrick has written the book “The Mom Test”, where he answers the question: How to talk to customers & learn if your business is a good idea when everyone is lying to you.

Reason #3: business problem vs. societal problem

Many startups today want to solve a big meaningful problem. In Sentar we felt that “back pain” was that huge societal issue, it made sense to dedicate the next five years of our lives to solve

In the world of startups, societal issues such as pollution are two folded. How do we minimise pollution for the greater good of society and make someone pay for it?

And back pain related to sedentary behaviour (sitting down) is a huge and important problem — for society that is. Just look at these numbers: – 80–85% of the world’s population experience Lower Back & Neck Pain (LBNP) during their lifetime – LBNP is the 2nd biggest cause of absenteeism (sick days) world wide – sedentary behaviour increases the risk of diabetes and cardiovascular diseases significantly

Hoy et al. (2010) estimated that LBNP costs the Australian society 9.1 billion USD each year! That’s a country of 25 million people. Researchers have proclaimed that “Sitting is the new smoking”.

But it’s a bit like the issue of pollution. Sure it is a big societal issue, and if we do not act to minimise it we, as a society, we will suffer the consequences of global warming. But there is not really any business in minimising pollution is there? Just as there might not be a direct link between lowering back pain amongst office workers and making money at the same time.

Sure, green business can be good business. But often environmental entrepreneurs find a creative way to make money on doing what they really want — saving the planet. Governments sometimes helps out by subsidising the business, making green business great business.

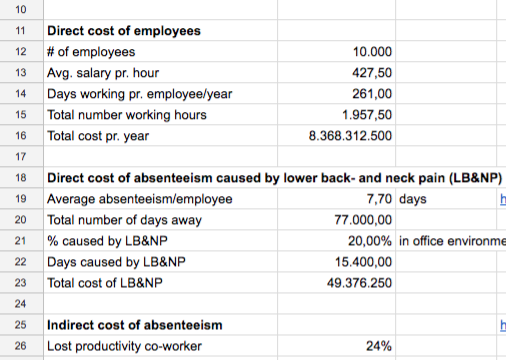

Sedentary behaviour cost health care systems billions each year in treatments and surgeries. But for now society does not reward businesses to make their employees sit less. In our case we found out that our customers struggled to figure out what sedentary behaviour represent in cost.

Here’s why:

- They did not track exactly why employees are sick (absent)

- They did not track performance accurately enough to measure the impact of lowering sedentary behaviour

- Total number of sick days were affected by multiple factors such as how busy the company were, national epidemics, the management’s performance etc.

- They had outsourced treatments (physiotherapists and chiropractors) to third parties providing them with 1–10 treatments for a lump sump fee

Of course we spent hours building a complex business case calculator for them, in which they could type inputs like; “Total employees”, “Average Salary”, “Current degree of yearly absenteeism” and so on. From this it would spit out the annual savings calculated from statistical reports on the percentage of total sick days caused by lower back and neck pain.

Our customers were almost more excited about this calculator than our real solution — hmmm ?

But what we found was a gap between these statistics and reality. At least none of our clients could give us a, just somehow exact, estimate of how much the problem we were trying to solve costed them.

Looking back we should have seen this as a huge warning sign. If our customers could not even estimate how expensive “our” problem was, it was probably not a big problem to them. Sure, we could aid them in building a specific business case, but if they had close to zero input to this, then the problem just wasn’t “top of mind”. If so, they would have tried to estimate something themselves and started to spend parts of their scarce budgets on competing solutions.

Do you want to read about the other 2 major mistakes we made?

This is the first article in a series of three about startup mistakes from the perspective of our own recent experience. Find the other two articles here: The pitfall of sunk costs and Not following a process every goddamn day.